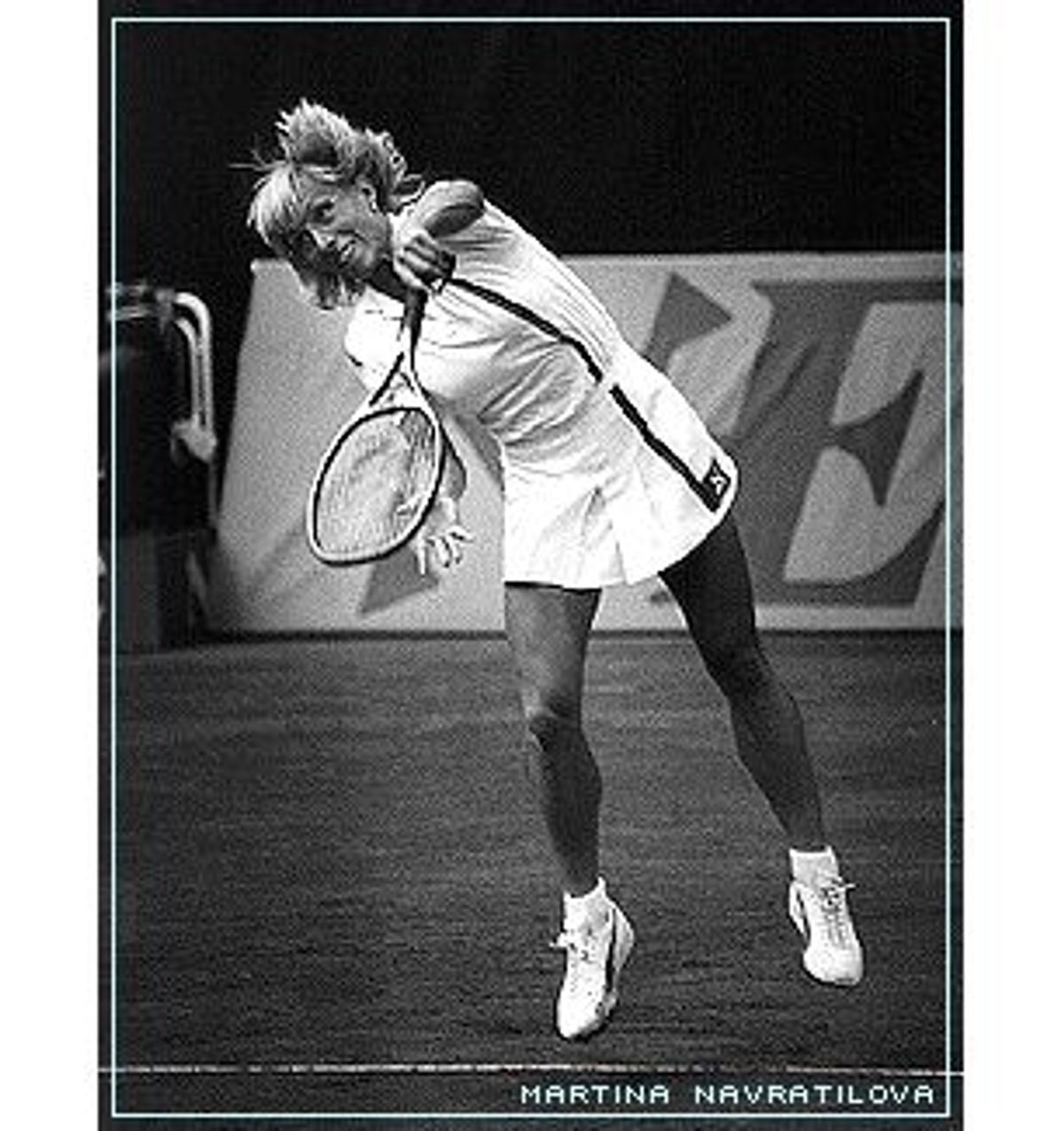

If it weren't for the quick cut to the tennis court, you might at first have trouble recognizing Martina Navratilova in the new Subaru commercials. Only six years have passed since she wrapped up the greatest career ever in women's tennis -- whether in terms of victories or just plain style -- but already Navratilova's tennis playing seems incidental, because there's simply no one out there now to remind us of her dynamic, attacking, serve-and-volley style (and that goes even for the amazing Williams sisters and for Navratilova's namesake, Czech-born Martina Hingis).

Navratilova, once too controversial for TV ads because she talked openly about her love of both men and women, is today as well known for her intelligence and willfulness as for her tennis game. This is the joke behind the TV spots, in which Navratilova plays off the idea that only men know cars. "What do I know about performance?" Navratilova says with easy, tart sarcasm, and then, at the close of the commercial, featuring her and other prominent female sports stars: "What do we know? We're just girls?"

Not so long ago, Americans saw Navratilova as the embodiment of otherness: the mysterious, left-handed Soviet-bloc athlete using her obviously state-manufactured prowess and strength to do battle with lovable blond American sweetheart Chris Evert and her wicked two-handed backhand. Like other athletes from Communist countries, Navratilova faced an inconsistent blend of bias -- hatred and scorn mixed with resentful awe. Yet as far back as when she was growing up outside of Prague, twig-thin and tiny but even then ready to swing big, Martina in many ways thought of herself as American.

"I was so stubborn, so independent, that I was more American than Czech, even as a little kid," she reflects in her autobiography, written in 1985 with New York Times sportswriter George Vecsey. "I didn't feel I belonged anywhere until I came to America for the first time when I was 16. I'm not a mystic about many things -- I tend to be pretty pragmatic about life -- but I honestly believe I was born to be American."

Now, long after she became a naturalized citizen, Navratilova's American identity is firmly established, so much so that when she shows up in the Czech Republic, as she did last year to receive a medal from Czech President Vaclav Havel, it's a big event. And that's fitting, because Navratilova is as American as Jay Gatsby, self-created in the way of people who take seriously the idea that they are free to live as they wish.

Navratilova retired in 1994 with a record 167 singles championships, still the all-time women's record, and was ranked No. 1 in the world seven different years, including 1982 to 1986 consecutively. She won the Australian Open three times and the French twice, but it was before the rowdy, vocal crowds at the U.S. Open (which she won four times) and the respectful, proper crowds at Wimbledon that she made her most enduring mark. Wimbledon intimidated her at first with its tradition, its all-white clothes and strawberries and cream, but she ended up winning there an amazing nine times, including every year from 1982 to 1987.

"Martina revolutionized the game by her superb athleticism and aggressiveness, not to mention her outspokenness and her candor," Evert told Women's Sports and Fitness magazine when Navratilova retired. "She brought athleticism to a whole new level with her training techniques -- particularly cross-training, the idea that you could go to the gym or play basketball to get in shape for tennis. She had everything down to a science, including her diet, and that was an inspiration to me. I really think she helped me to be a better athlete. And then I always admired her maturity, her wisdom and her ability to transcend the sport. You could ask her about her forehand or about world peace and she always had an answer. She really is a world figure, not just a sports figure."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Navratilova's parents divorced in 1959, when she was 3 years old, and Martina moved from a ski lodge in the Krkonose Mountains to her mother's childhood home in the village of Revnice, just outside of Prague. These were Communist times, of course, and people did not have their own tennis courts. But Navratilova's mother's family had once had a 30-acre estate, and when the Communists took power in 1948, they took the land and left the family the house and a red-clay tennis court in the yard.

Tennis history owes a lot to the Czech Communists' small show of restraint in leaving the court outside of what would be Martina's window, but the loss of so much of what had been theirs left a mark on the family. Martina would sneak into the grove across the street and steal apples, consciously seeking to reclaim a little of what was lost. "I think my mother and my grandmother carried a sense of litost, a Czech word for sadness, that I picked up, a feeling of loss at the core of their souls," Navratilova writes in her autobiography.

Agnes Semanska, Martina's maternal grandmother, a tennis player herself, had beaten the mother of Vera Sukova in a national tournament. (Sukova reached the finals at Wimbledon in 1962.) Martina was athletic even as a toddler, and still remembers zipping downhill on skis when she was 2. Showing the local boys she could compete with them in ice hockey and soccer also made an early impression. But tennis was impossible to ignore. Her mother and father (her "second father") spent most of their time at the town tennis club, except in winter, and Martina was given one of her grandmother's old wooden rackets. It had no grip tape, was a little crooked and was ridiculously oversized for puny little Martina, but even at age 4 she would spend hours hitting balls against the wall as her parents played matches.

"I remember the first time I played tennis on a real court," she wrote in her autobiography. "The moment I stepped onto that crunchy red clay, felt the grit under my sneakers, felt the joy of smacking a ball over the net, I knew I was in the right place. I was probably about 6 years old when that happened, but I can remember it as if it was yesterday."

Martina's father told her she could be a champion, and hit with her for hours every day. He pushed her hard, and could be tough and analytical about her technique, but he stopped short of becoming one of those tennis fathers or mothers who try to live their lives through their children. He made sure she was having fun and would say things like "Make believe you're at Wimbledon."

Martina was so boyish, short-haired and wiry, that when she turned 9 and her father took her to meet Czech champion George Parma for possible lessons, Parma looked at her warily and said, "How old is he?" Parma took her out and drilled balls all around the court, and she chased them down. Protigi and coach developed a close relationship, and Martina developed a big enough crush to wish she was old enough to marry him.

Parma had Martina ditch her two-handed backhand, which she had been using all her young life, so she could have more reach and make better volleys. He forced on her the good advice that a mastery of routine shots makes all the difference, and worked with her on strategy and the psychology of match play. Parma wanted her to have the foundation of training he never had, and the Czechoslovak system made that possible.

"In the mid-'60s, the communists could see the value of sports as a way of making people proud and keeping their minds off the less pleasant aspects of life," Martina would later write. "The Communists more or less emphasized a different sport in each country: weight-lifting in the Soviet Union, track and field in East Germany, gymnastics in Rumania, tennis in Czechoslovakia."

In 1968 she lived through the single largest event in Czechoslovakia until the country achieved its independence during the Velvet Revolution in 1989 -- the Soviet crackdown on the Prague Spring. The Czechs beat the Russians in ice hockey in the winter Olympics in France that year, Alexander Dubcek had people believing in the possibility of greater freedom and even an 11-year-old girl felt the excitement in the air. Martina was at a junior tournament in Pilsen -- famous for its beer -- when the Soviet tanks made their move the night of Aug. 20. As much as the Czechs tried to maintain an independent spirit -- unfurling banners like "Ivan, go home. Natasha has sexual problems" -- "socialism with a human face" was history and more than 100,000 defected in the next year, many of them prominent writers, artists and athletes.

"When I was 12 and 13, I saw my country lose its verve, lose its productivity, lose its soul," she writes. "For someone with a skill, an aspiration, there was only one thing to do: Get out."

But she kept working on her tennis, and she even believes her resentment of Russians made her a better player. Offended that a Russian she had defeated wouldn't shake her hand one time, Navratilova told her, "You need a tank to beat me." The same would be true of her opponents when she hit her peak on the women's tour a few years later.

"Martina is probably the most daring player in the history of the game," legendary TV analyst Bud Collins said when Navratilova retired. "She dared to play a style antithetical to her heritage without worrying about making a fool of herself. She dared to remake herself physically, setting new horizons for women in sports. And she dared to live her life as she chose, without worrying what other people thought of her."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

It wasn't so long ago that Navratilova ruled women's tennis; it just feels that way. Saying "Martina and Chrissy" has a way of making the late '70s feel current again. Navratilova and Evert were rivals and friends, and one of the greatest sports tandems ever. "We're matched like chocolate-or-vanilla, jazz-or-classical, two champions with opposing styles competing for limited space at the top of women's tennis history," Navratilova wrote in her book.

The two women played so many memorable games, they all roll together into one endless, up-and-down carnival ride. An intense, wild tennis match between opponents who know each other perfectly can have a transcendent appeal, but the best tennis, like the best novels or movies, has characters people feel they know, personalities who make us care. Navratilova and Evert did that like no one has since.

Navratilova had been Czechoslovakia champion, and she had played in West Germany and England in the West, and Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and East Germany in the Soviet bloc, but it wasn't until she traveled to the United States in 1973 as an unknown 16-year-old that her life in tennis really got started. Her serve-and-volley game made an immediate impression. She gave former Wimbledon champion Evonne Goolagong a good match before losing 6-4, 6-4, and in the first round of a tournament in Akron, Ohio, lost 7-6, 6-3 in her first match with Evert, who had reached the semifinals at the U.S. Open in 1971 and been a semifinalist at Wimbledon in 1972.

It was Navratilova's pairing with Evert that vaulted her into the realm of unforgettable sports stars. Evert did not just dazzle Navratilova with her talent, experience and easygoing personality, she also posed an obstacle that would eventually require the young Czech to reinvent herself. It wasn't until their sixth match, two years after their first meeting, that Navratilova finally beat Evert. But later that same year, they met at the U.S. Open and Evert won, 6-4, 6-4 -- one of many such victories in that early period that at one point gave Evert a 14-2 edge.

Navratilova was still just 16 when she returned from that first eight-week tour of the United States. She beat a top American, Nancy Richey, to make it to the quarterfinals at the French Open the next year before losing to Goolagong, and played in her first Wimbledon, the pinnacle of tennis. "Everything is Wimbledon," Navratilova would write. She soaked up the atmosphere and won two matches before succumbing.

The Czech authorities let her travel to the United States again in 1974 and in Orlando, Fla., she won her first professional tournament, beating Julie Headman, 7-6, 6-4, in the final. That was enough to give Navratilova a clear idea of what she wanted: a free, unfettered shot at success in America. There was just one small problem: She lived in a Soviet satellite state. Soon she was colliding with the Czech tennis authorities, who called her "too Americanized" and criticized her for being too friendly with Americans like Evert and the great Billie Jean King. Sukova, now the Czechoslovak women's coach, told Martina: "You've got to cool it. You'll get yourself in trouble and everybody else in trouble."

But by then Navratilova knew it was just a matter of time before she had to take action. She knew that at some point, she could lose her travel privileges, even though she was soon regularly winning tournaments. She made her firm decision to defect around the time of the 1975 U.S. Open, and spent most of that tournament sequestered in her hotel room with attorneys and FBI agents. After she lost to Evert in the semifinals, Navratilova met with the Immigration and Naturalization Service on Manhattan's Lower West Side and ended up having to flee her hotel room the next day, while her asylum application was still being processed, when news of her defection broke.

The Czechoslovak government condemned her, and would soon do its best to rub out all traces of her existence. Neither was the transition to life as an American easy for Navratilova, who was no longer Czechoslovakian but not yet American. By Wimbledon the year after she made her move, she was "a candidate for a nervous breakdown," as she put it. Back at the U.S. Open, exactly a year after the high jinks with the FBI and the INS asylum process, she dropped a first-round match to unseeded Janet Newberry, and broke down afterward, sobbing. Newberry said she'd never seen anyone so distraught.

The next day, she bought a house in Texas, so she could move from Los Angeles and begin turning herself into a polished pro athlete. She ran. She lifted weights. She watched what she ate. She dropped from 167 pounds to 144 over the course of the next year.

She was fit and confident and on a roll by 1978 when she started the year by winning 37 straight tournament matches and beating Evert for her first Wimbledon championship, which also vaulted her to her first No. 1 ranking. There were ups and downs, but the resolve and discipline that kicked in that first year in Texas renewed itself later when her career started faltering. She lost a match 6-0, 6-0 to Evert in 1981, the worst loss of her career, and soon began working out with Nancy Lieberman, a professional basketball player at that time. Even as the tennis press occupied itself with articles asking, "What's wrong with Martina?" Navratilova dropped her body fat to 8.8 percent and her weight back down, and this time was ready to keep working at it. She even consulted with a dietitian, something then unheard of and now routine among top athletes.

This was the Martina who would become so unbeatable that women's tennis became almost boring for a while. She worked with Dr. Renee Richards and former men's pro Mike Estep and just kept getting better, so much so that it seemed a shame she couldn't play the men. "My only regret is she didn't play on the men's tour," said Ilie Nastase when she retired. "I would have liked the chance to play her." But before she reached that highest plateau of her career, she had to face another huge disappointment -- losing the 1981 U.S. Open final to 18-year-old Tracy Austin, who wore Navratilova down in the third set, leaving her devastated. But she discovered something in her moment of despair.

"I was still crying when the announcer called my name for the runner-up trophy," she wrote. "But then something marvelous happened: The crowd started applauding and cheering. Their ovation lasted for more than a minute, and I stood there and finally started to cry, but I cried tears of appreciation, not sadness ... It was really strange, not like tennis at all, but really something you expect to see in opera, where the soprano steps out of her role on the stage for a curtain call, and the crowd cheers and throws roses. That's how I felt. They weren't cheering Martina the Complainer, Martina the Czech, Martina the Loser, Martina the Bisexual Defector. They were cheering me. I had never felt anything like it in my life: acceptance, respect, maybe even love."

Shares